BEGALI KEYS

Quest'anno è stato un anno particolare, tutto sommato positivo. Tra l'altro, ho avuto modo di conoscere più a fondo il mio amico Piero e l'ho un pò contagiato nel mondo dei fancazzisti. Purtroppo i suoi anticorpi sono molto resistenti e solo poche volte l'ho coinvolto nel dolce far nulla. Anche quando è libero dagli impegni, pensa sempre alla sua officina. Sul Mar Nero, però sono riuscito a portarlo sul green:

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/xapb50

Dopo il successo avuto al campionato mondiale di CW, un altra soddisfazione l'ha ricevuta con un articolo sul G.D.B:

Ecco un anteprima dello SCULPTURE MONO questo è solo un prototipo in alluminio, lo potrete ammirare alla Fiera di Montichiari:

Innumerevoli le recensioni su tutti i mezzi di comunicazione, in un articolo del Wall Street Journal, appare in fotografia il tasto più richiesto lo "Sculpture", nella foto con il radioamatore Chuck Adams

|

|

|

|

October 8, 2007 |

|

--- -. .

-- .- -. .----. ... -... .. -.. - --- ... .- ...- .

|

|

|

|

Michael M. Phillips |

|

Chuck Adams taps out a message. |

And, at the age of 15 -- inspired by his father, a ham-radio operator -- he taught himself Morse code from a book. At the time, ham operators had to transcribe Morse code at a rate of five words per minute in order to earn the most basic federal license. Soon young Mr. Adams was spending every night sending coded messages to anyone who could hear them, and eavesdropping on UPI news dispatches broadcast to ships.

Too Twangy

Many other radio amateurs use voice transmissions, but Mr. Adams preferred code, because of the challenge -- and because he thinks his voice is too high and his West Texas accent too twangy.

Mr. Adams completed a Ph.D., won tenure at the University of North Texas, worked high-powered jobs in the defense and computer industries, and dabbled in the professional poker circuit. But he never lost his love for Morse code.

The code is the creation of a painter, Samuel F.B. Morse, who needed a way to transmit messages over the telegraph that he and Alfred Vail had invented. In 1844, the men famously sent a transmission from Washington to Baltimore that read, "What hath God wrought?"

The telegraph soon replaced the pony express. As late as World War II, ham operators found themselves using their Morse skills as radiomen in the military. During the Vietnam War, POW Jeremiah Denton, later a U.S. senator from Alabama, blinked "T-O-R-T-U-R-E" in Morse code when his captors put him on television.

But over time, the telephone and satellites have rendered Morse code almost obsolete. "If the satellites go out and power goes out, Morse code can still get through," says Nancy Kott, president of a code club called FISTS -- someone who sends good code has "a good fist." "All we need is a battery and two wires to tap together, and we can communicate."

MORSE CODE

|

A |

.- |

|

B |

-... |

|

C |

-.-. |

|

D |

-.. |

|

E |

. |

|

F |

..-. |

|

G |

--. |

|

H |

.... |

|

I |

.. |

|

J |

.--- |

|

K |

-.- |

|

L |

.-.. |

|

M |

-- |

|

N |

-. |

|

O |

--- |

|

P |

.--. |

|

Q |

--.- |

|

R |

.-. |

|

S |

... |

|

T |

- |

|

U |

..- |

|

V |

...- |

|

W |

.-- |

|

X |

-..- |

|

Y |

-.-- |

|

Z |

--.. |

In February, the Federal Communications Commission eliminated the Morse requirements for ham-radio licenses. Mr. Adams resigned from a ham-operators organization because of what he saw as its flaccid defense of Morse code.

"It is a sad state of affairs when the U.S. doesn't even attempt to keep the language alive or give an incentive to work on it," says Mr. Adams.

Many of those who still know Morse code test their skills with a German computer game called Rufz, the standard for determining world transcription-speed rankings. Players listen to coded, five-character call signs, combinations of letters, symbols and numbers that identify individual license holders. The faster and more correctly they type them, the more points they score. (Transcribing regular text is much slower.)

Last month in Belgrade, Goran Hajosevic broke 200 words per minute -- an extraordinary pace. Mr. Adams is tied for eighth in the world, at more than 140 words per minute.

Scanning the list recently of the 60 fastest Morse coders under the age of 20, Mr. Adams spotted just two with American-issued call signs. "What this shows me is in the United States, we have no one who's interested in learning Morse code anymore," he lamented.

Mr. Adams and other Morse aficionados don't speak of dots and dashes; that imagery is too visual, and Morse is an aural language. So they prefer to describe the language in dits and dahs, the sounds of the short and long tones. A, for instance, is dit dah. B is dah dit dit dit, or simply dah dididit. Between two letters, the sender allows a three-dit silence. Between words it grows to seven dits.

'In the Zone'

Like all Morse experts, Mr. Adams rarely breaks signals down into letters, instead hearing complete words much as readers recognize words on a page. When he transcribes a message at high speeds, his fingers are five or 10 words behind his ears. When he is "in the zone" he isn't even conscious of what he is transcribing, he says. He has to read it later to understand the message.

When he listens to one of his books, the code is like a voice speaking to him. "It's like you don't count the i's when someone says Mississippi," he explains.

|

|

|

Paddle-style key and radio used to send Morse code. |

He produces his audio books to play at different speeds, depending on the expertise of the buyer. Ken Moorman's bedtime listening is Mr. Adams's 25-word-per-minute version of "The War of the Worlds," which he purchased for $10.50. "It's so much easier to pick up a microphone and yell," says Mr. Moorman, a 65-year-old retired electrical engineer in Williamsburg, Va., and a coder since 1957. "The people who do [Morse code] today do it because it's a lost art."

Earlier this year, Mr. Adams sent Barry Kutner, a 50-year-old ophthalmologist from Newtown, Pa., and another world-class coder, a 100-words-per-minute version of the book. To Mr. Adams's chagrin, Mr. Kutner wrote an email back pointing out that the gap between words was eight dits long, instead of the prescribed seven. At that pace, a dit lasts 1.2 one-thousandths of a second.

Much as he did growing up in Texas, Mr. Adams enjoys sitting in front of a gray radio, not much bigger than a hardcover book, and sending code with a $500, Italian, stainless-steel, paddle-style key that he operates with a pinching motion. With the slightest touch of his right thumb on one paddle, the key sends an audible dit. A touch of his right pointer finger on the other paddle sends a dah.

Keeping Busy

His wife, Phyllis, 62, doesn't begrudge him his long hours in front of the radio. "I'm just glad he has something to keep him busy," she says. "All my friends with retired husbands complain they follow them around the house all day."

One recent Sunday morning, Mr. Adams's radio came alive with Morse tones. It was a guy named Gary McClain in Pryor, Okla. The transmissions were pretty slow, just 22 words per minute.

Mr. McClain, a 65-year-old retired mill worker, learned Morse code in the Boy Scouts half a century ago. He had nothing urgent in mind; he just wanted to make contact with someone far away.

"Weather here is cloudy and chance of showers," he tapped, as Mr. Adams transcribed the words in a notebook.

Mr. McClain signed off, and the radio went silent. "It will eventually die," Mr. Adams mused. "I'll hate to see it go. I won't have anybody to talk to. I'll have to go back to reading."

L'articolo originale si trova a questo indirizzo: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB119161604206850468.html

Oppure in un articolo del New York Times appare in foto un Simplex:

Hudson/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

A worker at the Central Telegraph Office of the post office in London using Morse Code in 1932, which was soon replaced by teletype machines.

By MIGUEL HELFT

Published: December 27, 2006

It may be the ultimate S O S — Morse Code is in distress

Peter DaSilva for The New York Times

John Fore, left, and David B. Leeson, both members of the Stanford Amateur Radio Club at the station at Stanford University.

Peter DaSilva for The New York Times

With thumb and forefinger barely touching the two metal ends of a Morse paddle, a ham operator unleashes a stream of dits and dahs.

The language of dots and dashes has been the lingua franca of amateur radio, a vibrant community of technology buffs and hobbyists who have provided a communications lifeline in emergencies and disasters.

But that community has been shaken by news that the government will no longer require Morse Code proficiency as a condition for an amateur license. It was deemed dispensable in part because other modes of communicating over ham radio, like voice, teletype and even video, have grown in popularity.

While the decision had been expected, some ham radio operators fear that their exclusive club has been opened to the unwashed masses — and that the very survival of Morse Code is in question.

“It’s part of the dumbing down of America,” said Nancy Kott, editor of World Radio magazine and a field representative for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Metamora, Mich. “We live in a society today that wants something for nothing.”

A woman in a mostly male world, Ms. Kott is one of about 660,000 licensed ham operators in the United States and is the American leader of Fists CW Club, an organization that calls itself the International Morse Preservation Society. (An “open fist” was the hand position typically used by telegraph operators when sending Morse, which is sometimes called Continuous Wave, or CW. And in ham radio slang, someone who sends fine code is said to have a good fist.)

Within 48 hours after the Federal Communication Commission’s move this month to drop the Morse requirement, a discussion on www.eham.net ran more than 380 messages and 57,000 words long, the equivalent of a short novel. The postings were divided roughly evenly between those lamenting and praising the commission’s decision.

“CW is just another mode and should not be afforded any special priority over others,” wrote K4UUG, who like many radio aficionados identified himself online using his radio call sign. “Proficiency should not be required for those who do not wish to use the mode.”

As part of its decision to eliminate the Morse requirement, the commission made essentially the same point.

Inside a hilltop trailer above Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif., a couple of veteran coders seemed to be taking the commission’s decision in stride earlier this week. In a room cluttered with electronic equipment, they translated the dits and dahs that beeped in the background at dizzying speed, the chatter between someone in Canada, VE6NL to be precise, and someone off the coast of Antarctica, VP8CMH.

“It’s a bit like a foreign language,” said W6LD, whose real name is John Fore, a securities lawyer at Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, a prominent Silicon Valley firm. “You learn it and it’s fun to use it.”

With thumb and forefinger barely touching the two metal ends of a Morse paddle, W6NL, a k a David B. Leeson, unleashed his own stream of dits and dahs with the ease of a virtuoso, joining the global conversation. “I fell head over heels for amateur radio when I was 4 or 5 years old and heard Morse Code signals from afar at the station of a 14-year-old,” said Mr. Leeson, 69, a consulting professor of engineering at Stanford. “I still remember the thrill.”

The thrill turned into a hobby, and the hobby turned into a career in technology. In 1968, Mr. Leeson founded California Microwave, once a thriving telecommunications equipment company but now defunct. Now radio and Morse are just for fun, said Mr. Lesson, who is faculty adviser to the Stanford Amateur Radio Club, which once counted William R. Hewlett and David Packard as members.

Mr. Leeson and Mr. Fore are both active in radio contests, 48-hour competitions in which hams try to contact as many other hams as possible, often using Morse. Mr. Leeson has a station in the Galapagos Islands, where he goes several times a year with his wife, Barbara (K6BL), for contests. They once contacted as many as 17,000 other hams in a weekend. Mr. Fore, who is 50, and got his first license when he was 10, has a station in Aruba.

They embody the kind of utility-free passion for Morse that the futurist Paul Saffo said would ensure its survival.

“Freed from all pretense of practical relevance in an age of digital communications, Morse will now become the object of loving passion by radioheads, much as another ‘dead’ language, Latin, is kept alive today by Latin-speaking enthusiasts around the world,” Mr. Saffo, a fellow at the Institute for the Future, wrote in his blog.

Morse Code was first devised in the 1830s for use with the telegraph. It later became an essential part of civilian, maritime and military radio communications. But the military has largely abandoned its use in favor of newer technologies, and the Coast Guard stopped listening for Morse S O S signals at sea during the 1990s.

The F.C.C. first lifted the Morse Code requirement for entry-level licenses in 1991. It later dropped proficiency requirements for higher-level licenses to five words a minute, from 20. And after international regulations stopped mandating knowledge of it in 2003, it was only a matter of time until Morse Code was no longer required in the United States. The requirement will formally be phased out sometime next year.

The demise of the Morse requirement, however, could be a boon for ham radio itself. After the F.C.C.’s decision, the American Radio Relay League, an organization representing ham radio operators, said demand for information about radio licenses surged from about 200 in a typical weekend to about 500.

“We are very pleased to see that,” said David Sumner (K1ZZ), the league’s chief executive.

That is no consolation for the most avid defenders of Morse.

“There is something magical about being able to put two wires together and start going dit-dit-dit dit-dit,” said Ms. Kott, or WZ8C. “We are just going to have to get on the air and do what we do and hope for the best.”

L'articolo originale si trova a questo indirizzo: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/27/business/27morse.html?scp=9&sq=morse+code&st=nyt

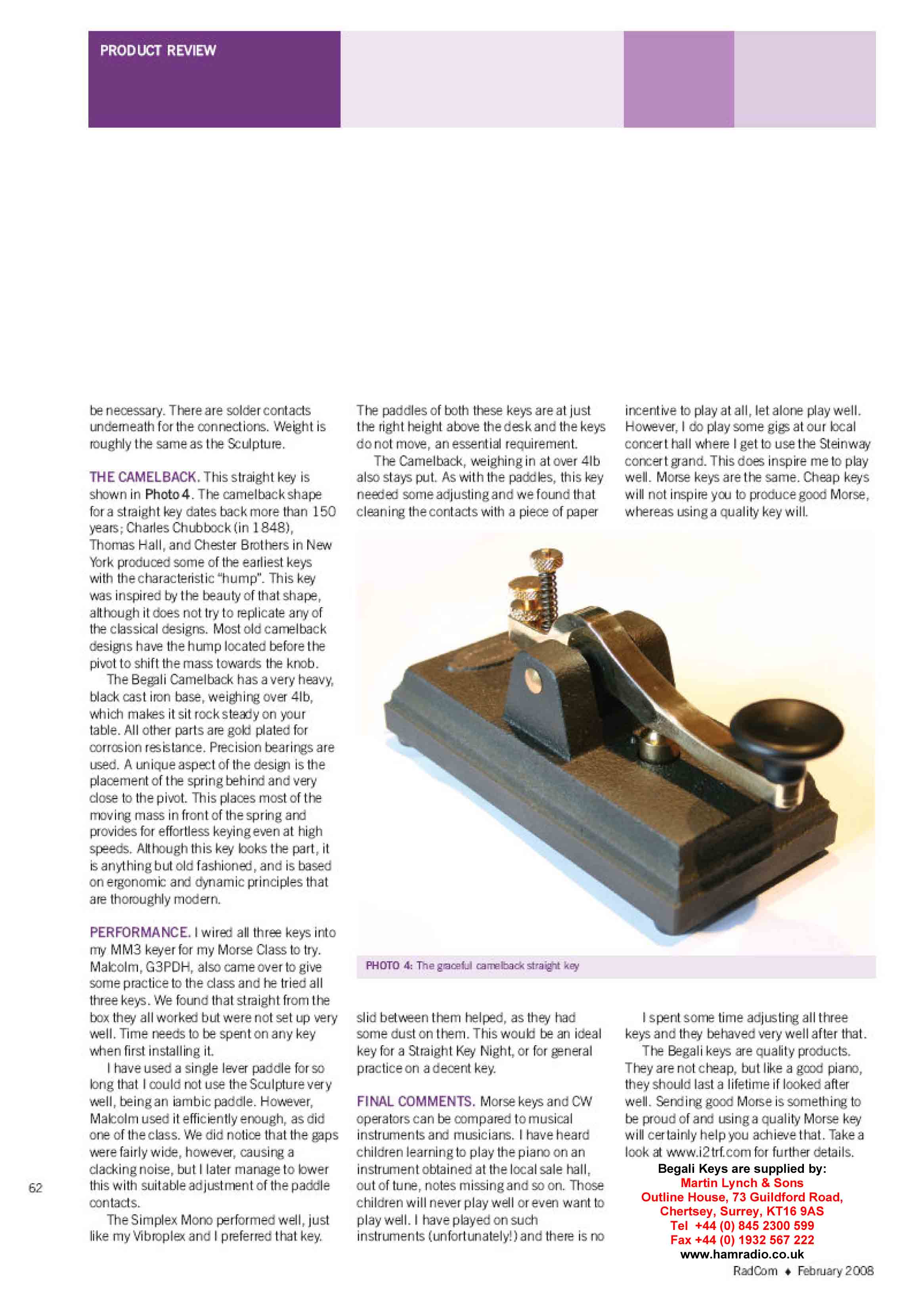

Un altro articolo da una rivista del settore in U.K.:

Articolo recente dal Sandusky Register, giornale del nord-centro Ohio:

E in ultimo dalla news letter Nr 332 dell'ARI di Milano:

Premio per il miglior prodottore tecnico per Radioamatori alla Fiera di Dayton.

Auguri Piero e tante di queste soddisfazioni.

73 de ik2uiq

ITC Manager

IARU HSTWG ARI Representative